|

|

by Tamra Reall, PhD, Field Specialist in Horticulture, University of Missouri Extension - Urban West

There are many ways to become an insect scientist, also called an entomologist. Entomologists, like Dr. Bug (me!), study the fascinating world of insects. In addition to studying insects, curiosity and education are key! Other useful subjects include math, chemistry, ecology, art, writing, and public speaking. Depending on your interests, here are some of the different kinds of entomologist you can become one:

Learn How Termites Talk! Termites use chemical trails to help nestmates find food and their way back home. Supplies:

What to do: 1.First, find your tiny team. Gently dig in moist soil near wood to find worker termites. Collect 5-ish with a paintbrush and put them in a container with a damp paper towel (keep it shady!). 2.On the paper, use a pen to draw simple shapes. 3.Using the paint brush, gently place a termite in the center of a shape and watch its path. Does it follow the line? 4.Repeat step 3 with different pens. Do the termites react differently? Observe and wonder: Can termites "smell" the pen ink? What might this tell us about how they communicate? See this experiment in action by clicking https://youtube.com/shorts/cscHDDX9e7k or scanning the QR code. Be a Water Strider Scientist! Water striders glide across the water's surface. Let's unlock their secret: surface tension! Supplies:

Skim the Science: 1.Fill the dish with water. 2.Gently place each object on the water. Does it float? 3.Touch the water near the object. Does it sink now? 4.If it still floats, add a little soap to the water Water Magic: Water has surface tension, like a thin "skin." This lets lightweight objects float, just like water striders! Touching the water disrupts this "skin," causing some objects to sink. Observe and wonder: What did you learn about floating objects? Being lightweight helps water striders to use surface tension. Water striders also have water-repellant hairs on their hind and middle legs to increase the surface area and help them glide on the water surface. Learn more about water striders here: https://mdc.mo.gov/discover-nature/field-guide/water-striders Be an Insect Inspector: Build Your Own Traps! Let's see what creepy crawlies live in your backyard! Build these simple traps and observe the fascinating insect world. Supplies:

Trapped!

Remember: Identify insects using apps like iNaturalist or ask your local University Extension for help. Check pitfall and bottle traps daily and release insects carefully. Be mindful of anything that can sting or bite! ~~~~ Did you know that there is a Kids Ask Dr. Bug video series? Check it out! https://bit.ly/KADBvideos Do you have questions for Dr. Bug? Send them to https://bit.ly/KidsAskDrBug To help her learn what you learn from this column, or to share feedback, please consider filling out this survey: https://bit.ly/KidsAskDrBugSurvey

0 Comments

Home to more than plants, kids ask Dr. Tamra Reall about the curious things found in the garden.

(Article used with permission from the Kansas City Gardener.) Are there really zombie cicadas? If you’re thinking about brain-eating zombies from the movies, then no. However, there are indeed periodical cicadas that have mind- and body-controlling fungal infections that take over and control their actions. While male and female periodical cicadas can be infected, when the males are infected, it causes them to act like a female who is receptive to a male looking for a mate. By making the cicadas interact with each other, the fungus can spread to other cicadas. If you see a periodical cicada that looks like they have a piece of powdery chalk as their abdomen, this is the fungus. Sometimes, nearly the entire abdomen is missing, and the cicada will still be moving around! While this may seem like something straight out of a sci-fi movie, it’s really a fascinating example of how nature finds ways to survive and reproduce. It also shows us how connected everything in the ecosystem is. "Zombie cicadas" might sound scary, but they're an important part of the web of life! So, the next time you see a cicada, take a closer look. There is a lot we can learn from even the weirdest things in nature! Is it bad for my dogs to eat bugs? You might be surprised to learn that the occasional bug on the menu isn't a big deal for most dogs. In fact, for some curious pups, chasing and catching a fly or cicada is just part of the fun of being a dog! In most cases, an insect or two won't cause any harm and might even provide a little extra protein boost. However, there are a few things to keep in mind:

If you're ever unsure about a particular insect, it's always best to err on the side of caution and avoid having your dog eat it, and/or consult your veterinarian. Why are you called Dr. Bug? Kids gave me that nickname years ago because my last name is a bit tricky. And, let's face it, Dr. Bug is way cooler, right? Plus, it goes perfectly with my job as an insect scientist! Speaking of cool bugs, did you know there's now a "Kids Ask Dr. Bug" cartoon on YouTube (https://bit.ly/KADBvideos)? Check it out on the @MUExtensionBugNGarden channel – it's full of fun facts about all sorts of creepy crawlies! Why do some insects, like ants and bees, work together as a team? Great observation! This is the kind of observation that scientists make to learn more about the world around us. If only some kinds of insects work together, you may have noticed that most insects do their thing on their own, or solitary. Solitary means that they don’t really interact with others of their species except for when it’s time to start the next generation. On the other hand, ants and honey bees are uniquely able to work together as a colony. This is because they are eusocial, or a superfamily, meaning that these related insects all live together and have specific responsibilities, including a queen and sometimes a king. Termites, paper wasps, and yellowjackets are more examples of eusocial insects. Colonies of eusocial insects may have hundreds, thousands, or even millions of individuals working together. The ability to work together gives these insects a huge advantage and they are able to do things that individual insects can’t do. Examples include building a giant anthill or making enough honey to feed the colony for an entire winter. Eusocial insects are able to build amazing homes, find food more efficiently, guard the colony, and take care of their young. If the colony is attacked, some may die while defending the colony, but there are many more who can keep the colony going! And, to work together well, communication and specialization are really important! Special chemicals called pheromones are used for much of the communication. Pheromones are scent-instructions, or smelly messages. Ants and termites leave pheromone trails to tell the colony where to find food and how to find the way back home. Colony members have a special scent that is unique to the colony so the guards at the nest entrance make sure only nestmates enter. Alarm pheromones are released, and vibrations are sounded throughout the colony if an invader has entered! Honey bees also use pheromones to protect the hive and let all the bees know that queen is alive and healthy. Foraging honey bees also use sound, scent, and dancing vibrations to tell hive mates where to find the best flowers for pollen and nectar. Tamra Reall, PhD (@MUExtBugNGarden) is a horticulture specialist for MU Extension – Urban West Region. For free, research-based gardening tips, call 816-833TREE (8733), email [email protected], or visit extension.missouri.edu. Do you have questions for Dr. Bug? Send them to https://bit.ly/KidsAskDrBug To help her learn what you learn from this column, or to share feedback, please consider filling out this survey: https://bit.ly/KidsAskDrBugSurvey

Termites work together as a team to break down wood and create a large nest for their colony.

Image: T. Reall Do you love gardening and want to share your passion with others? Become an Extension Master Gardener and join a vibrant community dedicated to learning and teaching the best practices in horticulture.

The MU Extension Master Gardener program offers:

Limited spots available! Apply by August 2nd. Cost: $200 (scholarships available) More information: http://www.mggkc.org/about-us/become-a-master-gardener/ or contact Tamra Reall ([email protected]) by Cathy Bylinowski, Horticulture Instructor, University of Missouri Extension- Jackson County I frequently look at other people’s yards and gardens and admire their flowers, trees, and shrubs. If I see a plant that is new to me, I try to figure out what it is, if it will grow in my yard, and where I can buy one! This spring, take some time to enjoy the flowering trees and shrubs in your neighborhood, parks, and green spaces around you. If you see some you like, now is a great time to figure out what they are and if they will grow in your yard. Spring is also a good time to plant new flowering trees and shrubs. They provide enjoyment for years to come. Here are several spring-flowering trees and shrubs that grow well in our part of Missouri: Serviceberry- (Amelanchier arborea) Serviceberry, native to Missouri, is an attractive small tree with smooth gray bark. It grows on wooded slopes. The snowy white flowers appear in early spring before anything else in the woods has leafed out. Tasty berries appear in June and leaves turn pink and orange in the fall. Unfortunately, invasive, non-native Callery Pears (Bradford Pear being one type) are blanketing open areas. Do not mistake the white flowers of Callery Pears for Serviceberry! Flowering dogwood- (Cornus florida) White flowering dogwood is a popular native flowering tree. Johnson County, Missouri is the nearest natural occurrence of this tree in our region. It will grow in our region, if it is put in a protected, part- shade location. Growth is fairly slow. Their branches are open and horizontal, with a rounded mature shape. They can get up to 30 feet tall. Their spectacular white bracts appear before leaves. Small, red fruit persist in fall and attract songbirds. It has lustrous, scarlet foliage in fall. They can be used as specimens, in masses or naturalized under larger trees, preferring moist, humus rich, slightly acidic soils. Avoid planting in hot, dry places. Use an organic mulch under the tree. Dogwoods need water during drought. Old or injured specimens are subject to insect borer damage. Eastern redbud (Cercis canadensis) Redbuds can get up to 30 feet tall. The clusters of purplish pink small flowers appear before leaves emerge. Heart-shaped leaves turn yellow in fall. Plant redbuds as specimens, in masses, or naturalized at the edge of woods. They are hardy in sun or part shade and tolerate a wide range of soils. Common Lilac (Syringa vulgaris) Lilac is one of the best known and most widely planted of all the introduced, flowering shrubs. Lilacs are worth having in your yard or garden for their once-a-year display of incredibly fragrant flowers. For the classic lilac fragrance, plant Common Lilac or one of its hybrids. Lilacs get up to 9 feet tall. Lilacs perform best in well-drained soils in full sun. Plants should receive at least six hours of direct sun each day for maximum bloom. Proper pruning is necessary to keep lilacs attractive and to promote flower production. After the plant becomes established, about one-third of the old stems should be removed each year. Older lilac stems may be attacked by borer insects. Flowering Magnolias (Magnolia soulangiana) These magnolias look like beautiful pink clouds in the spring. The only drawback is that the flowers can be damaged by spring freezes. You might enjoy the scented flowers so much that you are willing to take the risk of flowers turning brown after a spring freeze. There are cultivars that bloom later in the spring with pink, purple, or yellow flowers. Some magnolias can get to 30 feet tall. Plant in protected parts of your yard away from southern exposures. These are only some of the many trees and shrubs, native and introduced, that offer beautiful spring color. Contact Extension Master Gardener Hotline for more information:816-833-TREE (8733) – 24-hour voicemail [email protected] Flowering or Saucer Magnolias provides spectacular color in the spring.

From Pixabay by Ceeline by Linda Geist, University of Missouri-Extension

The phrase “waste not, want not” goes back to a time when the essentials of life were difficult to obtain, but it continues to be good advice today, says University of Missouri Extension horticulturist David Trinklein. It applies even to ashes produced this time of the year by wood-burning fireplaces and stoves. “When collected and spread on the garden, wood ashes are an excellent and free source of calcium and other plant nutrients,” Trinklein said. Wood ashes are highly alkaline. As a safety precaution, wear protective glasses, gloves and a dust mask when spreading on the garden. Ashes from burning cardboard, trash, coal or treated wood of any type may contain potentially harmful materials and should not be used on the garden. Ashes are the organic and inorganic remains of the combustion of wood. Their composition varies due mainly to the species of wood. As a rule, hardwood species produce three times more ashes and five times more nutrients than softwood species, he said. Since carbon, nitrogen and sulfur are the elements primarily oxidized in the combustion process, wood ashes contain most of the other essential elements required for the growth of the tree used as fuel. By weight, wood ashes contain 1.5%-2% phosphorus and 5%-7% potassium. If listed as a fertilizer, most wood ashes would have the analysis of 0-1-3 (N-P-K). Calcium content ranges from 25% to 50%. Because of the high calcium content, it’s probably best to think of wood ashes as a liming material to adjust soil pH rather than a regular fertilizer to supply an array of nutrients, said Trinklein. The ideal pH range for most garden plants is about 6.0 to 6.5. When soil pH falls below this range, certain essential mineral elements become less available to the plant. Since garden soils tend to become more acidic as plants take up nutrients, periodic adjustment to decrease soil acidity (increase pH) is necessary. Most wood ashes have an acid neutralizing equivalent of about 45%-50% of calcium carbonate (limestone). In other words, it takes about twice the weight of wood ashes compared with limestone to cause the same change in soil acidity. For example, if soil tests indicate you need 5 pounds of limestone per 100 square feet of garden area to raise the soil pH to an acceptable level, you would need 10 pounds of wood ashes to make the same change, Trinklein said. Apply small amounts of wood ashes to the garden on a yearly basis to supply other nutrients such as phosphorus and potassium. Trinklein recommends a soil test every two to three years where light applications are made on a regular basis. Excessive application of wood ashes can lead to a buildup of pH above the optimum range. This can result in other nutritional problems because of reduced nutrient availability at high pH values. Wood ashes not applied to the garden immediately should be stored under dry conditions. Ashes piled outdoors lose most of their potassium in a year’s time due to leaching from rains. Additionally, weathered wood ashes’ ability to act as a liming agent also is greatly reduced. Because of the fine nature of wood ashes, they cannot modify soil structure and, therefore, are not considered a soil conditioning agent. The carbon compounds that act as a soil conditioner when sawdust, leaf mold or compost are applied to garden soil, for the most part, have been consumed by the fire. For more reliable, research-based information on gardening, contact Master Gardeners of Greater Kansas City Gardeners Hotline- 816-833-TREE (8733) or email- [email protected] by Tamra Reall (@MUExtBugNGarden) is a horticulture specialist for MU Extension – Urban West Region (Article used with permission from the Kansas City Gardener.) Get ready for a magical cicada spectacle this spring! Billions of buzzing insects from periodical cicada Broods XIII (13) and XIX (19) are emerging in April and May. Last seen together in 1803, they won't appear together again for another 221 years. In Missouri, we will just be seeing Brood XIX, while Brood XIII will be mostly in northern Illinois. I hope you will join the excitement, enjoy the rhythmic buzz, and marvel at nature’s spectacular show! What is the difference between periodical cicadas and the cicadas that come out every year? Periodical cicadas are like nature's timekeepers, following a mysterious, prime number schedule that scientists are still learning about. Having the longest life cycle in the insect world, periodical cicadas seem to magically appear together every 13 or 17 years. This is why their genus name is Magicicada! They spend most of their lives underground as nymphs feeding on the sap of tree roots. Then, as if waiting for the perfect moment, groups of Magicicada species, called a “brood,” emerge together all at once. These small, black cicadas with red eyes appear in such large numbers that they can cover trees. These clumsy fliers are easily captured by birds, squirrels, raccoons, and even dogs and cats. With so many emerging at the same time, many will survive to lay eggs for the next generation emerging in another 13 or 17 years later. Another fascinating feature of these insects is that the males sing together to attract females. In contrast, the large, green cicadas we see each summer have a shorter life cycle of 2-5 years and are known as annual or dog-day cicadas as some become adults every year. While these cicadas also sing in the trees, they give solo performances and do not synchronize like the periodical cicadas. Are periodical cicadas everywhere in the world? Although annual cicadas are found on every continent except Antarctica, periodical cicadas are only found in the eastern half of North America. Scientists do not know why they aren’t found anywhere else. There are four species of periodical cicadas in Brood XIX and these will emerge in Missouri, Indiana, Illinois, Kentucky, Maryland, Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Arkansas, Oklahoma, Tennessee, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, and Mississippi. In Brood XIII, there are three species, and they are emerging in Illinois, Iowa, Indiana, Wisconsin, and possibly Michigan. Brood XIX, also known as the Great Southern Brood, emerges every 13 years, and Brood XIII (the Northern Illinois Brood) emerges every 17 years. 17-year broods tend to be in the northern states with cooler temperature zones, and 13-year broods tend to be in the warmer, southern states although there is a lot of overlap between 13- and 17-year broods. Why do cicadas shed their skin? Cicadas shed their skin to grow bigger. Like other insects, they have a hard outer covering called an exoskeleton. As they grow, their old exoskeleton becomes too small, so they shed it in a process called molting leaving behind old exuviae and growing new, larger exoskeletons. Do periodical cicadas hurt people, animals, or plants? Cicadas may land on people, but they won’t eat you – you don’t taste, feel, or smell right to them. That said, if one lands on you, gently brush it off, just in case the cicada is curious about what you might taste like! But, the cicadas can affect trees. Females lay their eggs in small twigs in trees. Large healthy trees aren’t harmed in the long term by this, although there may be dead twigs that fall after the cicadas are gone. Smaller trees can be damaged or even killed if not protected. Consider covering small, or newly planted, trees with a fine mesh material or cheesecloth to protect them during the 4-6 weeks the cicadas are out. Why do they make that loud sound? Males use a drum-like structure on their abdomen called tymbals to sing their loud, repetitive buzzing song, attracting female companions. A female will fly to the males and respond by quickly flicking her wings together if she likes his song. Periodical cicadas can be tricked by other vibrating sounds. They may be attracted to people mowing their lawns or using power tools. Periodical cicadas are loud! Because the males sing together, the buzzing sound can reach up to 100 decibels, which is as loud as a hair dryer, lawn mower, or a motorcycle. Consider wearing hearing protection if you will be outside for more than 15 minutes when the cicadas are singing to protect your hearing. What happens to cicadas after they mate and lay eggs? After mating, female cicadas lay their eggs in the branches of trees. They use a sharp ovipositor to make tiny slits in the bark, where they deposit their eggs. Males die soon after mating and females die after laying their eggs. A couple of weeks later, the eggs hatch and young cicada nymphs fall to the ground and burrow into the soil where they'll spend the next 13 or 17 years before starting the cycle all over again! ~~~~ Did you know that there is a Kids Ask Dr. Bug video series? Check it out! https://bit.ly/KADBvideos Do you have questions for Dr. Bug? Send them to https://bit.ly/KidsAskDrBug To help me learn what you learn from this column, or to share feedback, please consider filling out this survey: https://bit.ly/KidsAskDrBugSurvey Known for their red eyes, cicada eyes actually can be several colors. Photo courtesy of Gene Kritsky, Mount St. Joseph University

by Cathy Bylinowski, Horticulture Instructor, University of Missouri Extension EMGs of the Master Gardeners of Greater Kansas City chapter are here to help you learn to grow. We are volunteers under the auspices of University of Missouri Extension. We help you learn more about gardening by providing researched-based information and reliable best practices for a wide range of gardening topics. We receive fourteen weeks of training by MU Extension horticultural specialists and then pass that knowledge on to you and your families at educational gardening projects, children’s programming, and special events in Clay, Jackson, and Platte Counties. You can find information about our chapter and volunteer program by going to our website- mggkc.org or by finding and following our Facebook Page– Master Gardeners of Greater Kansas City. How EMGs can help you:

To subscribe to these YouTube videos, click on the big red Subscribe button from the site referenced above. Once you subscribe to a channel, any new videos published will show up in your Subscriptions feed.

Saturday, March 9 is the first Annual Spring Fling Gardening Celebration at the Young School at Truman Heritage Habitat for Humanity, 505 N. Dodgion Avenue, Independence, MO 64050. Free event for interested gardeners and families.

· Do you have a gardening question and need help? - Send your questions to our Hotline by calling or emailing our team- 816-833-TREE (8733) – 24-hour voicemail or [email protected] Please include your county, phone number and any pictures that would help us assist you in your email)

Have more questions? Contact Horticulture Instructor Cathy Bylinowski, [email protected] for more information. Extension Master Gardeners of Greater Kansas City maintain a Food Pantry Garden at 18th and Broadway where they demonstrate how to grow a wide range of vegetables and herbs and donate produce to local food pantries and community kitchens. Photo credit: Master Gardeners of Greater Kansas City

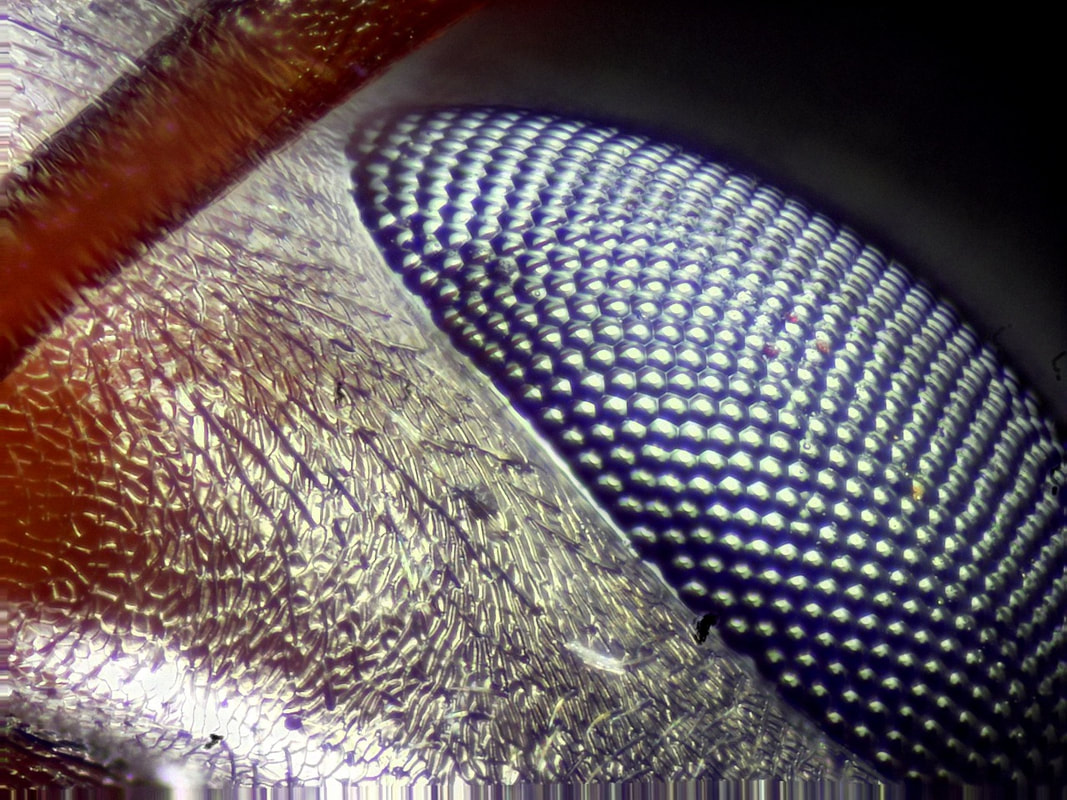

by Dr. Tamra Reall, University of Missouri Extension (Article used with permission from the Kansas City Gardener.) Did you know that there is a Kids Ask Dr. Bug video series? Check it out! https://bit.ly/KADBvideos When will start seeing butterflies again? As the days lengthen, temperatures rise, and flowers begin to bloom, butterflies gradually reappear. Different butterfly species emerge at varying times. Some may flutter as early as March or April, while others wait for warmer weather and abundant flower nectar. Butterflies adopt different strategies to survive winter, either as eggs, caterpillars, pupae (known as chrysalises), or adults. They seek refuge in protected spots like under leaves, in tree crevices, under bark, or in sheds. As temperatures climb, they emerge, seeking flowers for food and places to lay eggs. Certain butterflies depend on specific flowers, appearing only when those plants bloom. For instance, Monarch caterpillars solely feed on milkweed, though as adult butterflies, they sip nectar from various flowers. This means they seek milkweed to lay eggs but linger longer if other flowers are available. So, keep your eyes open! Once consistently warm weather arrives, these vibrant creatures will dance around in gardens, parks, and even your backyard. By planting flowers that attract butterflies, you might create your own butterfly haven, encouraging them to visit. Can bugs see me? Insects perceive the world around them in fascinating ways, different from how we do! Most insects might sense you as part of their environment, but they don’t see you in the same way we see each other. Insect eyes are intriguing—typically, they typically have two compound eyes made up of tiny parts called ommatidia. The size of these compound eyes can vary; for instance, an ant has fewer ommatidia than a dragonfly. This means an ant’s compound eyes are smaller, while a dragonfly's larger eyes allow it to see more at a time, which is especially useful when hunting while flying. Additionally, many insects have three simpler eyes on their heads called ocelli, which sense light and dark, or even polarized light, helping insects orient themselves and find their way. Some insects, like butterflies and bees, have extraordinary eyesight for arthropods They can distinguish shapes and colors, even colors invisible to us. If you're in their way, wearing colors resembling flowers, or carrying something attractive such as food, they might notice you or even land on you. However, insects like ants or certain beetles perceive the world through shadows or movements rather than detailed images. Beyond eyesight, insects have incredible sensing abilities. Mosquitoes rely on detecting carbon dioxide and heat to 'see' you. Others use their antennae to feel air vibrations or detect heat and chemicals (known as pheromones) to navigate their surroundings. In short, insects might not see us in high definition, but their impressive senses allow them to detect our presence in their own unique and intriguing ways. Can ants swim? Ants might not swim like we do, but they're pretty clever when it comes to water! They have tiny hairs on their bodies and because they're so small and light, the surface tension of water helps them stay on the surface without sinking. But when there's a flood, the whole ant colony needs to stick together. They hold onto each other using their legs, antennae, and even their mouths, creating what's called an 'ant raft.' The ants at the bottom support the ones above, keeping them safe until they find dry ground. They're so good at this that they can live like this for weeks! Sometimes, when ants need to cross water, they use the same linking skill to create bridges. It's all about teamwork! Check out this link for more information: https://b.gatech.edu/48JM6ZB . So, even though ants don't swim like we do, they've got incredible skills to handle water and keep themselves safe when things get wet. What can we do to help insects during the winter? Helping insects during winter is fun and easy to do! One of the easiest things to do is to leave leaves in your yard. Think of leaves as a cozy blanket for insects—they use them to stay warm and protected from the cold, rain, and snow. Another great way to help is by keeping parts of your garden a little messy. It might sound funny, but having areas with old logs, twigs, or piles of leaves gives insects hiding spots to stay warm. Letting plant stems stand tall provides hiding places, almost like tiny hotels, especially for native bees that lay their eggs in these stems. Leaving them intact offers shelter until it gets warmer, helping the bees without putting them at risk from pests that might invade containers where we keep these stems. By doing these simple things, you're giving insects a helping hand to stay safe and cozy until spring returns. Do you have questions for Dr. Bug? Send them to https://bit.ly/KidsAskDrBug To help me learn what you learn from this column, or to share feedback, please consider filling out this survey: https://bit.ly/KidsAskDrBugSurvey Image: A close-up view of an insect's eye where each tiny bump is called an 'ommatidium.' When all these bumps team up, they make what's called a 'compound eye,' helping the insect see lots of things around them. Image by Woodturner, Pixabay. by Dr. Tamra Reall, University of Missouri Extension

There are yellow, orange, red ladybugs - are they all actually ladybugs? Yes, they are all part of the ladybug family! Ladybugs, also called ladybirds, belong to a big beetle family. Ladybugs are oval-shaped and can be yellow, orange, or red like what you have found. They can also be gray, black, brown, or even pink! Sometimes they have spots, but not always. So, if you see a little beetle with an oval body and different colors like yellow, orange, or red, it might just be a ladybug, even if it doesn’t have spots. Ladybugs come in lots of beautiful colors! Why can bugs and spiders live inside our house during winter, but there aren’t any insects outside in the cold? Think of our homes as cozy hideouts for insects and spiders during winter! Just like we find our houses warm and comfy, these critters seek refuge from the freezing cold outside. Those who come indoors may not be built to be active outside in the chilly temperatures, so they move inside where it's warm and there's food. Our homes offer refuge for them to stay snug until it gets warmer outside. You might be happy to know that not all arthropods can survive the winter indoors because our homes are usually too dry for them. Common arthropods that come inside are nonnative ladybugs, stink bugs, or spiders. If you find them indoors, you can gently scoop them up and release them back outside. Or you can use a vacuum. But watch out—some insects, like stink bugs, can give off a funky smell if vacuumed up! Also, after cleaning, remember to empty the vacuum and take out the trash to keep these uninvited guests from returning! How do insects survive when it gets so cold or warm in the same week? Insects are experts at handling changing weather. As fall and winter arrive, some insects enter a dormant stage called diapause, almost like hibernation, to prepare to survive harsh conditions. Many insects rely on light to let them know what season we are in, rather than the temperature because it can change so much during our winters. So, even if it warms up for a day or two, they will stay in their dormant stage. Other insects can adjust to the changing temperatures and emerge or become active as the weather is favorable. Still, others do not survive when it gets cold enough, so they die off for the winter. Then, either their offspring emerge in the spring, or others of their species migrate here from southern climates as the weather warms up here. Insect abilities to change behaviors, life stages, and even body functions help them handle changing weather without skipping a beat. How does climate change affect bugs? Climate change affects insects in some big ways. Because of their short lifespans, many insects are super adaptable, but even they struggle when things get too out of whack. With the changing weather patterns, insects might have to move around more to find food and the right conditions to live in. Unfortunately, some insects can end up causing problems by moving into new places where they shouldn't be, like invasive pests crashing in where they don't belong and eating plants we don’t want them to eat. Brown marmorated stink bugs and Japanese beetles are examples of invasive pests. You know how some insects and plants work together, such as bees and butterflies that pollinate flowers that create fruit? Well, the changing climate can affect that, too. Pollinators and their favorite flowers might not sync up like they used to, meaning flowers might bloom before the bees or butterflies have emerged to pollinate them. It's like they're playing different tunes in a band and it gets confusing! This is a big issue, and it will take a lot of cooperation between governments, corporations, and organizations. However, we can help! Planting more flowers is awesome because it gives pollinators more food and we get more beautiful flowers. Using IPM (that's Integrated Pest Management, a fancy term for controlling pest insects without using too many chemicals) is very helpful too for the survival of beneficial predators who capture pests, so we don’t have to. Turning off lights at night is good because it helps insects that rely on the stars, moon, or Milky Way at night to navigate. So, creating more bug-friendly places for insects to live is a win-win. We can make a difference by helping our arthropod friends adapt to a changing world! What's something strange about insects? One incredibly unusual thing about insects is their diversity in communication. While many insects use sounds to communicate, some have really unique methods. For instance, treehoppers communicate by vibrating stems, honey bees dance to tell their sisters where to find the best nectar and pollen, and fireflies use light to attract mates. Also, many insects use pheromones, which are like special perfumes, to signal danger, attract partners, or create trails to find food and their way home. Their communication methods are exceptionally diverse and fascinating, showing just how creative nature can be! Do you have questions for Dr. Bug? Send them to https://bit.ly/KidsAskDrBug To help me learn what you learn from this column, or to share feedback, please consider filling out this survey: https://bit.ly/KidsAskDrBugSurvey Did you know that there is a Kids Ask Dr. Bug video series? Check it out! https://bit.ly/KADBvideos by Cathy Bylinowski, M.S. Horticulture, Horticulture Instructor

University of Missouri Extension- Jackson County, MO For decades, the USDA plant hardiness zone map has been the "gold standard" for gardeners and other growers wanting to know if a perennial plant (herbaceous or woody) will survive the cold temperatures of a typical winter in their area. Additionally, scientists incorporate the plant hardiness zones as a data layer in many research models, such as those predicting the spread of exotic weeds and insects. Recently, the USDA unveiled a revised version of the map, updating the 2012 edition of the document. The new map was jointly developed by the USDA's Agricultural Research Service and PRISM, a highly sophisticated climate mapping technology developed at Oregon State University. The revised version of the map is more accurate and contains greater detail than prior versions. As a U.S. Government publication, the USDA Plant Hardiness Zone Map as a graphic is not copyrighted and is in the public domain. Map graphics may be freely reproduced and redistributed. Available online at https://planthardiness.ars.usda.gov/, the 2023 map is based on 30-year averages of the lowest annual winter temperatures at specific locations. It is divided into 10-degree Fahrenheit zones and further divided into 5-degree Fahrenheit half-zones. The 2023 map incorporates data from 13,412 weather stations compared to the 7,983 that were used for the 2012 map. Plant hardiness zone designations represent what is known as the "average annual extreme minimum temperature" at a given location during a particular time period. In the case of the 2023 map just released, that period was 30 years. The annual extreme minimum temperature represents the coldest night of the year, which can be highly variable from year to year, depending on local weather patterns. In other words, the hardiness designations do not reflect the coldest temperature ever recorded at a specific location, but simply the average lowest winter temperature for the location over a specified time. Low winter temperature greatly influences the ability of a perennial plant to survive in a particular area. Like the 2012 map, the 2023 version has 13 hardiness zones across the United States and its territories. Each zone is broken into half zones, designated as "a" and "b." For example, zone 6 (which includes most of Missouri) is divided into half-zones 6a and 6b. When compared to the 2012 map, the 2023 version reveals that about half of the country shifted to the next warmer half zone, and the other half of the country remained in the same half zone. That shift to the next warmer half zone means those areas warmed somewhere in the range of 0-5 degrees Fahrenheit. However, some locations experienced warming in the range of 0-5 degrees Fahrenheit without moving to another half zone. Once a draft of the map was completed, it was reviewed by a team of climatologists, agricultural meteorologists, and horticultural experts. If the zone for an area appeared anomalous to these expert reviewers, experts doublechecked the draft maps for errors or biases. These national differences in zonal boundaries are mostly a result of incorporating temperature data from a more recent time period. However, temperature updates to plant hardiness zones are not necessarily reflective of global climate change because of the highly variable nature of the extreme minimum temperature of the year. Additionally, some changes in zonal boundaries are also the result of using increasingly sophisticated mapping methods and the inclusion of data from more weather stations. Consequently, map developers involved in the project cautioned against attributing temperature updates made to some zones as reliable and accurate indicators of global climate change. The latter usually is based on trends in overall average temperatures recorded over long time periods. In addition to the map updates, the Plant Hardiness Zone Map website was expanded in 2023 to include a "Tips for Growers" section, which provides information about USDA research programs of interest to gardeners and others who grow and develop new varieties of plants. For more information about MU Extension Horticulture Programs in Jackson County, contact Horticulture Instructor Cathy Bylinowski, [email protected]. |

Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

Grain Valley NewsGrain Valley News is a free community news source published weekly online. |

Contact Us |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed